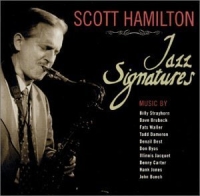

Composers write songs, musicians play them. Truth or truism? It took the pop world a few generations to acknowledge the singer/songwriter, but in jazz, the player/writer was always a recognized force. Here, Scott Hamilton -a Concord artist for more than twenty years- places his stamp on several tunes of some of jazz's best players.

Composers write songs, musicians play them. Truth or truism? It took the pop world a few generations to acknowledge the singer/songwriter, but in jazz, the player/writer was always a recognized force. Here, Scott Hamilton -a Concord artist for more than twenty years- places his stamp on several tunes of some of jazz's best players.

With typical candor, Scott explains: "I usually fight the idea of concept albums, because they limit the material, and may end up sounding forced and uncomfortable. But this date was just a happy coincidence. I'd been playing all these tunes with this quartet last year. Most are numbers that John Bunch and I worked up on our annual Christmas gig at London's Pizza Express. When it came time to record something new, I really wanted to use John, Dave and Steve; we toured the continent to very good public reaction."

A little digging into personal history shows that Scott's coming up with this present repertoire has been a lifelong research project. The Hamiltons lived on the East Side where dad Robert, a painter, taught at nearby Rhode Island School of Design. Their house overflowed with art on the walls and music in the air. Scott would commandeer the upright piano in the hall, and proudly play his latest pieces for all who'd listen.

"When I was eight" recalls Scott, "I started clarinet lessons with Frank Marinacchio of the Rhode Island Philharmonic. He was a wonderful, legit clarinetist and I got to hear him play a little jazz on a gig. I studied a few years, but never tried to play jazz. But I was already listening to Johnny Hodges and Charlie Parker."

Scott was soon wailing on tenor saxophone with guys like guitarist Fred Bates, bassist Phil Flanigan, and drummer Chuck Riggs. Providence in the 1970s no longer had the Celebrity Club, a rough-and-tumble bar where you could see Bill Doggett, Gerry Mulligan, Count Basie, Dinah Washington. But it did have Alarie's, a semi-upscale white restaurant for pianists like Mike Renzi; Bovi's Town Tavern for Duke Bellarie, and Fred Grady was still a beacon of bop and swing on late-night radio. Still, Scott and friends idolized the tenor sax led small bands of the swing era, and stood as stalwart throwbacks to an earlier age.

"I listened to tenor sax players for years before I began playing seriously" recalls Scott. "Ben, Hawk, Lester, Bud Freeman. When I took up tenor sax at 16, I was particularly interested in Gene Ammons, Illinois Jacquet, Arnett Cobb, Lockjaw Davis, Red Prysock, Jimmy Forrest, Paul Gonsalves, and Fred Phillips. They're still the guys I listen to. Nothing compared to seeing a great player live. The times I saw Illinois play in the early 70s in Boston, are still my most truly thrilling musical experiences. Later in New York, I heard Zoot Sims and Stan Getz, who made great impressions on my playing."

Scott owned the reverence and keen ear for the sounds of Ben and Hawk, and the melodies of Illinois and Byas that he exhibits here, albeit with more savvy and suavity.

Strayhorn's masterpiece "Raincheck" starts like a riff tune, but then takes a sly slide into 16+16 song form with a hooting tag. Scott refers to Ben Webster in both content and tune, and John Bunch and Dave Green have their says.

Scott treats the Brubeck favorite "In Your Own Sweet Way", written early (1952) in his long, mellowing career, and ekes Zoot-like heat from his choruses. John's choruses span Teddy Wilson pizzazz and Hank Jones charm. The tag is played amoroso, with smears.

Waller's waltz is a waltz, a lively one, with Steve Brown whacking rimshots and tom-tom accents, as well as a capable solo. "I've recorded Jitterburg Waltz with Bucky Pizzarelli" says Scott, "but John's arrangement is so strong, we felt it was like an entirely different tune."

"If You Could See Me Now" excels a sweet ballad moan. "I've always loved Sarah Vaughan's recording" says Scott, "and I've been trying to learn it for years."

"Move" moves in forward bop fashion speedily to its conclusion, propelled by Steve Brown's snappy stick-work. Long in Scott's repertoire but premiered here on an album, it's by drummer Denzil Best, bet heard for fine brushwork in George Shering's early quintets.

Scott affords "When Lights Are Low" it's composer's wonted jaunty manner and elegant melodicism, so far as to inserting, on his last eight bars, a typically Cartesque flippant fillip. John takes a tasty bite, and Scott and Steve engage in lusty exchanges before all exit politely.

"Byas A Drink" is a variation on "Stomping at the Savoy" made in the 1940s under various titles; the riff was used years later by Clifford Brown and Max Roach.

"You Left Me Alone" is one of the first ballads I ever learned to play" recalls Scott. "Illinois wrote it in the 40s and recorded it with an all-star band in an arrangement by Tadd Dameron, who may have had a hand in this arrangement. I never had the nerve to record it before, as Illinois played it so definitively. I feel like I've figured out a way now to put a little of myself into it without losing it too much of Jacquet's original version. The number is meant as a tribute to the tenor player who I've always admired at most."

Hank Jones wrote "Angel Face" for a 1947 Coleman Hawkins date; Lucky Thompson and Milt Jackson recorded it in the 1950s, as one of Hank's most beautiful songs.

"The ringer here is John's Bunch" claims Scott. "John wrote this years ago, but it came out sounding so natural, we had to include it."

Actually, John's inclusion is a perfect capper, a bluesy bit of personal history from a composer who's been first and foremost a solid piano player. He's worked the big bands of Woody Herman, Benny Goodman, Maynard Ferguson, Buddy Rich, played hard for Zoot Sims and Al Cohn, and led his own tight bunches. John signes his closing stomper with a boogie flourish.

And thus have the moving fingers of veterans Scott and John, and youngsters Dave and Steve, played for us yet and another chapter in the book of jazz.

Since its inception in 1991, when they played their first gig together under the tony lawfirmish moniker of Medeski Martin & Wood (at the historic Village Gate in New York City), t his talented triumvirate has demonstrated an uncommon chemistry on the bandstand along with an almost unquenchable desire to play strictly on the improvisational edge and in the moment. As Rolling Stone's David Fricke once urged readers, "Go out on a limb with them; you'll always find a reason to dance".

Since its inception in 1991, when they played their first gig together under the tony lawfirmish moniker of Medeski Martin & Wood (at the historic Village Gate in New York City), t his talented triumvirate has demonstrated an uncommon chemistry on the bandstand along with an almost unquenchable desire to play strictly on the improvisational edge and in the moment. As Rolling Stone's David Fricke once urged readers, "Go out on a limb with them; you'll always find a reason to dance".