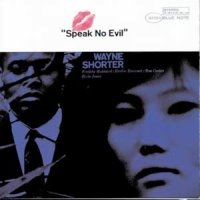

Wayne Shorter - Speak No Evil (1964)

Wayne Shorter has never taken the conventional approach to his career. His exceptional gifts as a saxophonist and composer has never been combined with a self-effacing stance that has set him apart from the outset. Where his contemporaries were grabbing every opportunity to record as leaders and chomping at the bit to form their own working bands, Shorter took a far more measured and audacious approach. Despite his stature as the most original and profound of the tenor saxophonists to emerge after Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane, and his similarly elevated status as a composer of uniquely original music, Shorter remained with Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers from 1959 to 1964; then he continued to ignore the call of leadership and joined Miles Davis. Shorter's personal discography was similarly modest. Before signing a contract as a solo artist with Blue Note around the time he left the Messengers, he could only claim a pair of albums for Vee Jay under his own name.

Fortunately, what most listeners considered the long overdue collaboration of Shorter and producer Alfred Lion took place at a period of rapid growth and prolific output for the saxophonist. Speak No Evil, Shorter's third Blue Note session in eight months, captures a pivotal moment in his evolution. His tenor playing, clearly formed by both Coltrane (the urgent tone and bold harmonic choices) and Rollins (thematic continuity and frequently broad humor), had rather facilely been considered a variation on Coltrane's work by some, and the appearance of Coltrane stalwarts McCoy Tyner and Elvin Jones plus former Coltrane bassist Reggie Workman on Shorter's previous Blue Note dates only underscored the comparison. Jones is once again present here; but the rhythm section is completed in this instance by Herbie Hancock and Ron Carter, Shorter's new associates in the Miles Davis quintet. Hancock and Carter bring a more open, space-conscious attitude to the music, one that Shorter into different areas without in any way diminishing the integrity of Jones's contribution. For his part, Shorter reveals a deeper lyricism and a more elegant use of unusual melodic shapes and harmonic extensions. Without sacrificing any power, his work had grown more poetic. His writing was evolving as well, "fanning out" as he puts it in his typically insightful comments to annotator Don Heckman. Shorter had already proven capable of retaining his compositional individuality while creating material for the specific needs of Art Blakey, and he would soon repeat this feat with the music he wrote for Davis. Here he is writing for himself, and the singular balanace of harmonic complexity and melodic grace, of assertion and calm that had marked such pieces as "Black Nile" and "Armageddon" (from Night Dreamer) and "Yes or No" (from JuJu) reached an even more exalted plateau with the six works heard here. The imagery, which Shorter clearly had in mind as indicated by his comments on the material, is conveyed in sound pictures that are no less apt for their structural unorthodoxies; and the overall themes of folklore and legend are realized as much by what Shorter leaves out as by what he includes. In these respects, and in such moments as the incredible opening tenor saxophone note on "Infant Eyes", it is tempting to claim the influence of the new boss on Shorter's music. Yet Shorter's ideas (what Joe Zawinul would call "the new thinking") were already headed in this direction eight months earlier on his Blue Note debut Night Dreamer, and Davis is on record as having sensed a kindred yet autonomous spirit in Shorter's music from his earliest days with Blakey.

The saxophonist could not have asked for more sympathetic musicians that the ones he recruited for this session, including his former Messengers mate Freddie Hubbard. Shorter paid them the respect their talents deserved by conceiving a program of challenging original music, and the band in turn honored him by meeting the challenge with total mastery. Together they created a body of music that has inspired musicians and listener s for over three decades, and which is supplemented in the latest RVG Edition of the album with a previously unissued take of "Dance Cadaverous". Jean Sibelius's Valse Triste, the composition that inspired "Dance Cadaverous", was coincidentally recorded by Shorter less than three months later in a sextet version, and can be heard on the Blue Note album The Soothsayer, where Hubbard and Carter are also present.

No comments:

Post a Comment