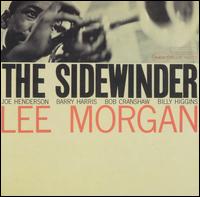

Lee Morgan - The Sidewinder (1963)

The gloss that Leonard Feather's liner notes provide Lee Morgan's career in the period immediately preceding The Sidewinder disguises what was the most dispirting stretch of the trumpeter's life. In the throes of a drug habit and after the Spring of 1961, no longer a member of Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, Morgan spent two years in a kind of career limbo. What little recorded evidence exists, such as his January 1962 Take Twelve album for Jazzland, indicates that Morgan's trumpet playing remained impressive; but his dependency kept him from regular work, and a number of other young trumpet players including Don Cherry, Don Ellis, Freddie Hubbard and Booker Little stepped into the breach and attracted the public's attention.

The gloss that Leonard Feather's liner notes provide Lee Morgan's career in the period immediately preceding The Sidewinder disguises what was the most dispirting stretch of the trumpeter's life. In the throes of a drug habit and after the Spring of 1961, no longer a member of Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, Morgan spent two years in a kind of career limbo. What little recorded evidence exists, such as his January 1962 Take Twelve album for Jazzland, indicates that Morgan's trumpet playing remained impressive; but his dependency kept him from regular work, and a number of other young trumpet players including Don Cherry, Don Ellis, Freddie Hubbard and Booker Little stepped into the breach and attracted the public's attention.Morgan's plunge into obscurity was so emphatic that, while back at home in Philadelphia, he reportedly heard a jazz radio program offer a Lee Morgan memorial tribute.

Fortunately for Lee Morgan and for jazz, he rallied; and Alfred Lion was there to document Morgan's new, rededicated self. The trumpeter had not been a Blue Note contract artist since 1958, having signed a deal with the Chicago Vee Jay label before his lone effort on Jazzland, yet he maintained a Blue Note presence from 1958-1961 through his work with Blakey and on his own 1960 album Lee-Way (made with Vee Jay's permission). Proof that Morgan was ready to move forward again was first heard on two Blue Note sessions from 1963 where he appeared as a sideman, Hank Mobley's No Room For Squares and Grachan Moncur III's Evolution. A month to the day after the Moncur album was taped, Morgan returned to Rudy Van Gelder's studios to record his own The Sidewinder.

What resulted was a surprise commercial hit. The title track took off, cracking the Billboard charts and ultimately serving as the soundtrack for an automobile advertising campaign. Morgan's attractive blues line, with the plunching sustained vamp that Barry Harris contributed to the arrangement and the clever harmonic wrinkle described in the original liner notes, transported the trumpeter from his recent nadir to the Hot 100. While it obviously had a significant impact on Morgan's career, "The Sidewinder" also encouraged Alfred Lion to attempt to duplicate this success with other artists in the Blue Note family. Rhythmically assertive, often over-extended opening blues tracks on subsequent Blue Note albums became the norm, though they rarely rose to Morgan's level of either inspiration or sales.

This fallout combined with sheer familiarity has left many listeners with negative feelings about "The Sidewinder" in particular and The Sidewinder in general. For them, a fresh listen should clear away the stale air of countless imitations, because the title track is filled with glorious playing. These musicians understood how to create a blues groove with feeling and intelligence, and the choices they make (Henderson's repeated figure in his second chorus and Harris's use of octaves when the piano solo begins, to cite two examples) provide lessons in how to effectively structure an improvisation that communicates. The rapport displayed throughout the album is a sign that important professional connections had been made, connections that in the case of Morgan and Higgins played themselves out over many subsequent Blue Note albums. Henderson's ability to galvanize other musicians' dates was announced in no uncertain times -his solo on "The Sidewinder" presages the similarly monumental tenor choruses he would lay down on Horace Silver's "Song For My Father" 10 months later- and the Harris/Cranshaw/Higgins rhythm section was reunited on Dexter Gordon's memorable 1965 album Gettin' Around.

Morgan's articulate descriptions of the music and the players plus Feather's astute analysis of the individual performances require only two additional comments. One concerns the alternate take of "Totem Pole", which might have sounded perfectly acceptable for the release if we did not have the superior master take. Hearing both in sequence illustrates how the slightest adjustments can lift a performance from the very good to the exceptional.

The second point concerns Lee Morgan the composer. When Morgan first recorded for the label as a leader between 1956-1958, he left the writing to others. After joining the Jazz Messengers, where he shared the front line with prolific composers Benny Golson, Hank Mobley and Wayne Shorter, and where Art Blakey always encouraged his sidemen to create original material, Morgan compositions began appearing with greater frequency, yet he still looked to others for the bulk of material on his own albums. Morgan's Jazzland LP was one of the first on which he wrote a majority of the tunes, and The Sidewinder found him responsible for all of the music for the first time.

So this album also announced that the new Lee Morgan was also a talented writer, a quality that would stand him a good stead on his subsequent Blue Note recordings.

No comments:

Post a Comment