Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers - Moanin' (1958)

"Staying with the youngsters", a credo Art Blakey espoused from the bandstand of Birdland five years earlier, was reaffirmed in no uncertain terms on this album. The drummer had celebrated his 39th birthday three weeks before entering Rudy Van Gelder's studio for the return of the Jazz Messengers to Blue Note, following the group's brief affiliaion with Columbia, World Pacific, Savoy, Elektra, Bethlehem and RCA. This was a new group, with members seperated in age by nearly two decades; yet Blakey rose to the challenge much as the equally venerable Miles Davis did a few years later when introducing his ESP band of young players. In both cases new blood bred a new era, as well as leading in the present instance to one of the most beloved albums in jazz.

"Staying with the youngsters", a credo Art Blakey espoused from the bandstand of Birdland five years earlier, was reaffirmed in no uncertain terms on this album. The drummer had celebrated his 39th birthday three weeks before entering Rudy Van Gelder's studio for the return of the Jazz Messengers to Blue Note, following the group's brief affiliaion with Columbia, World Pacific, Savoy, Elektra, Bethlehem and RCA. This was a new group, with members seperated in age by nearly two decades; yet Blakey rose to the challenge much as the equally venerable Miles Davis did a few years later when introducing his ESP band of young players. In both cases new blood bred a new era, as well as leading in the present instance to one of the most beloved albums in jazz.Excepting Pittsburgh native Blakey, this was an all-Philadelphia edition of the Messengers that found each sideman coming into his own. The precocious trumpeter Lee Morgan, no longer either a teenaged phenom or under the shadow of Dizzy Gillespie in the latter's trumpet section, had blossomed into an astounding stylist, and his power and expressive brilliance here sustain the maturation documented in the previous year on his own Blue Note sessions The Cooker and Candy. Bobby Timmons, himself only 22 yet a label familiar since his Cafe Bohemia session with Kenny Dorham, also emerged here from the ranks of fluent Bud Powell disciples to the ranks of a recognizable stylist whose affinity for the sanctified (as a soloist, and even more importantly as a composer) was critical in defining the era's soulful zeitgeist. Jymie Merritt's work was less familiar to jazz listeners of the time, yet (as a Leonard Feather's original notes make clear) his decade-long apprenticeship in rhythm and blues, blues, mainstream jazz and modern jazz had formed an approach to the bass that was a model of intelligent melodic choices, steadfast time and selfless strength. Notwithstanding the contributions of Morgan, Timmons and Merritt, there is no disputing that Benny Golson defined this edition of the Messengers. Three months short of his 30th birthday and the veteran of affiliations that overlap those of his hometown friend and contemporary John Coltrane, Golson was extremely well prepared to serve as a musical director of the group. Golson's playing and writing had been featured in the recently dissolved Gillespie orchestra that also included Morgan, as well as on several of Morgan's early Blue Note albums; but his contributions here are even more imposing. It was Golson who recruited his fellow Philadelphians for service with Blakey over the course of 1958, and while the sanctified Timmons composition "Moanin" became the album's runaway hit, it was Golson who was responsible for the majority of the material. He met the challenge of spotlighting the leader with the substantial "Drum Thunder Suite" (which delivers a wealth of melodic material while also creating a context for Blakey's exceptional mallet work) as well as the infectious "Blues March", which did as much to establish Blakey's trademark shuffle groove as "Moanin". The Messengers' "March" quickly eclipsed the original record version of the tune, which Blue Mitchell had cut with Philly Joe Jones drumming for Riverside four months earlier. Golson's more lyrical side comes through on "Are You Real" in the tradition of such earlier long-lined efforts as "Just By Myself", and the magnificent "Along Came Betty", as indelible a melody as any Golson has penned and perfectly orchestrated and executed to boot. These four compositions, as least two of which are classics, represent a level of output that was commonplace for Golson in the late fifties -and with "Moanin" added create a bounty of original material that any bandleader would envy. Golson's instrumentalist matched the earlier impact of Horace Silver and anticipated the contributions of such future Messengers as Wayne Shorter, Bobby Watson and Donald Brown. Timmons, who like Morgan served more than one term with the Messengers, would later supplement his more modest yet equally pivotal contribution to the Blakey book with "Dat Dere" and "So Tired".

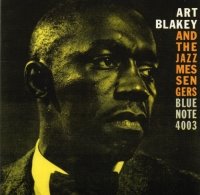

None of this in any way diminishes Blakey's personal triumph here. Much like the dignified cover portrait by Buck Hoeffler (rather than Blue Note mainstay Frank Wolff), the album presents a definitive image of the drummer-leader, one that gave new emphasis to the strutting dance-oriented figurations in Blakey's arsenal. Some commentators were upset with this stress on the backbeat, although both the results here and in further editions of the band demonstrate that Blakey was still ready to lead more straight-ahead charges and delve further into the music's African and Afro-Latin sources. What the backbeat really delivers here is the complete Art Blakey, which makes this collection (originally known simply as Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers) one of the essential chapters in the history of jazz rhythm, and therefore, jazz itself.

No comments:

Post a Comment