Jazz is not where you find it; jazz is everywhere, and Wynton Marsalis has consistently played it the world over for the last 25 years. He has led large and small bands in public and private situations across America, through Europe, Russia, Asia, Australia, Alaska, Canada, the Caribbean, South America and North Africa. Marsalis knows that the language of jazz is a lingua franca; when you swing, play the blues, deliver the romantic mood of the ballad, or lay into Latin rhythms, there is always a body of listeners ready to hear jazz as the spiritual elixir that it is. None of the talking of any sort means as much to a musician as the emotional force, the bond of soul and feeling, that gathers heat in the air when sound and the need to be moved meet. Then the space of performance and its circumstances are remade in the inimitable way we only expect from the invisible art of music.

Jazz is not where you find it; jazz is everywhere, and Wynton Marsalis has consistently played it the world over for the last 25 years. He has led large and small bands in public and private situations across America, through Europe, Russia, Asia, Australia, Alaska, Canada, the Caribbean, South America and North Africa. Marsalis knows that the language of jazz is a lingua franca; when you swing, play the blues, deliver the romantic mood of the ballad, or lay into Latin rhythms, there is always a body of listeners ready to hear jazz as the spiritual elixir that it is. None of the talking of any sort means as much to a musician as the emotional force, the bond of soul and feeling, that gathers heat in the air when sound and the need to be moved meet. Then the space of performance and its circumstances are remade in the inimitable way we only expect from the invisible art of music.

The quality of such occasions accounts for why Marsalis has been selling out clubs and concert halls throughout his career as a leader. The endless, standing ovations, the packed dressing rooms of well-wishers and autograph seekers, the many presents brought by listeners, the small army of students he has inspired or taught or given instruments, and the family dinners to which he has been invited, all add up to encouragements to continue on his chosen task, which is to deliver the artistry and the feeling of jazz wherever and whenever he can.

The performance here is, as are all Marsalis recordings, a culmination of where he was at the time of documentation. It was captured at what is an almost annual winter performance at the House of Tribes on East 7th Street in New York's Lower East Side, a section of Manhattan where jazz, poetry, and theater have been presented in alternative situations for more than five decades. The performance space at the House of Tribes is very small but the sound is superb and the audience comes expecting to have its soul boiled in the hot oil of deep feeling. That audience is made up of all colors and is from all backgrounds and religions, a common feature of Lower East Side. For all of their differences, the people there have one thing in common; they love the propulsion of swing as it arrives in the sound of jazz. Theirs is a desire for the timeless quality of joy that the artistry of jazz packs into every second as the cold, formlessness of the moment is overcome by the heat of human personality and the refinement of empathetic interaction. Somebody could say they come looking for a groove, and somebody else could say that when Wynton Marsalis is at the House of Tribes, they get just what they are looking for -and as much of it as they can stand.

Those unaware of the expansiveness of Marsalis's career might be surprised to find him playing in a low-income neighbourhood for an audience of no more than 50 people. They would find that surprising because they know he is one of the biggest stars in the world of jazz and could command a substantial fee at any high style room or concert hall in New York City. Such people would be unaware that Marsalis comes from a lower-class community in New Orleans and has always been willing to support any organization that seeks to offer art to the people. In short, Marsalis has never been a doily afraid of the grease and the gravy on the table. He, like all great jazz musicians, is from the people and brings the message of the people, which is the fundamental good news of life. That is the optimism that defines the struggle at the center of the blues, the universal desire to meet dreams in the temporary forms of flesh and blood, or to present the sorrows and revelations of life as one has known them.

Of the House of Tribes, Marsalis says "It's a small community space where they can have theater. It has the type of feeling that those places have in the South. It is a grass roots situation. The people are devoted to keeping the community in touch with art. You can feel the dedication in the air. These kinds of places are all over the world and they exist for the same reason. People make them happen, regardless of money or attention or any of the things that we are often told you have to have in order to do something. For me, playing at the House of Tribes is like being at home, back in the environment of pure dedication, the kind of feeling that makes you want to become an artist".

"The audience at the House of Tribes is of all ages but that audience has that thing in common that is always true of jazz audiences. They come to hear people play, and they come to swing and have a good time. You can hear it in their responses, which are not cliché imitations of people having a good time. This is the sound of an actual good time, which makes you want to play more and play better. The audience can always give you that".

Though we were not there, we can now experience, over and over, first-class contemporary jazz deep in the blue pocket of swing and full of the creations one expects of its very best players. Greg Osby says that Marsalis is the most original and comprehensive trumpet player to arrive in jazz since Woody Shaw, and Shaw himself revealed his accurate sense of the future in something he told Maxine Gordon about the younger trumpet player. While they were listening to him in the concert, Shaw said he was absolutely sure that Marsalis was destined not only to take the trumpet to new heights, but that he would elevate the making and presentation of jazz music as well. Given all that Marsalis has achieved on every plane, that has proven to be true. But this recording is not about the breadth of Marsalis, it is about nothing other than playing jazz. In that context, Marsalis's extraordinary sophistication continues to deepen the power of his art while delivering it with the greatest command of his instrument since Dizzy Gillespie and Booker Little. "Green Chimneys" and "Donna Lee" should convert any doubters. The heat, sweep, scale, and substance of Marsalis's thematic inventions reiterate, at almost every captured moment, that he is, as Betty Carter once said to him "the destinity of the music. The music needed him. He had to appear, and he eventually did".

Wess Anderson, as made clear on "Green Chimneys" is a startlingly original master of the alto sax. His other equally original features prove him the kind of improvisor we hear very little of at this time of academic school boys playing memorized patterns. Though a young man, Anderson is the best version of old school; he is a genuine melody maker of the first order, heavy in his harmony, and glowing in his rhythm. "Above all" Marsalis says, "Wess has heavy soul. It goes deep but it's also bouyant, and he loves to swing all night. He and I have invaded jam sessions all over the world. Wess Anderson is always ready to play and spread that good feeling. That's why musicians and listeners love him".

"Green Chimneys" also reiterates the fact that Eric Lewis is another of the fantastic piano players that Marsalis has introduced to the jazz world. Lewis is possessed of a talent that expresses itself free of the Herbie Hancock and McCoy Tyner methods that have become perhaps too common among the less imaginative of the younger piano playeres. Kengo Nakamura and Joe Farnsworth are two of the most prominent rhythm section players of the day. They have control of their instruments, which means they never play too loud and throw off the balance of the band. They know how to listen, support, and drive. They are top of the line professionals with artistic sensibilities. The same can be said of guest percussionist Orlando Rodriguez.

When you put that all together, you get everything a jazz lover needs; swing, melodic invention, harmonic surprise, rhythmic freshness, and a collective sense of improvising impassioned and logical music on the wing, surely the great performance gift that jazz has brought to music. Enjoy this indelible hot scoop of soul. It was made amongst the people, and for the people, which means that the music had you in mind.

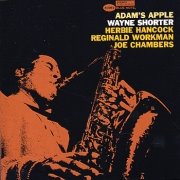

No slight on the four musicians who directly contribute to making Adam's Apple such a memorable experience, but hearing this intriguing program of music in light of subsequent history brings to mind three additional associates of Wayne Shorter who were not present at the February 1966 session.

No slight on the four musicians who directly contribute to making Adam's Apple such a memorable experience, but hearing this intriguing program of music in light of subsequent history brings to mind three additional associates of Wayne Shorter who were not present at the February 1966 session.